Late May 2013

Sailing into a large contemporary city is a wonderful and rather anachronistic thrill. It can also feel a bit daunting, for contemporary urban ports like Vancouver contain many sorts of obstacles, challenges and marine traffic, from kayaks to tankers to float planes, all moving at different speeds and in different directions. Since we’d as yet not sailed into Vancouver, we chose a day of rather calm winds and seas for our trip, looked over our charts and cruising guides, and carefully consulted the 2013 edition of that essential annual publication for Northwest boaters, Ports and Passes: Tides, Currents and Charts.

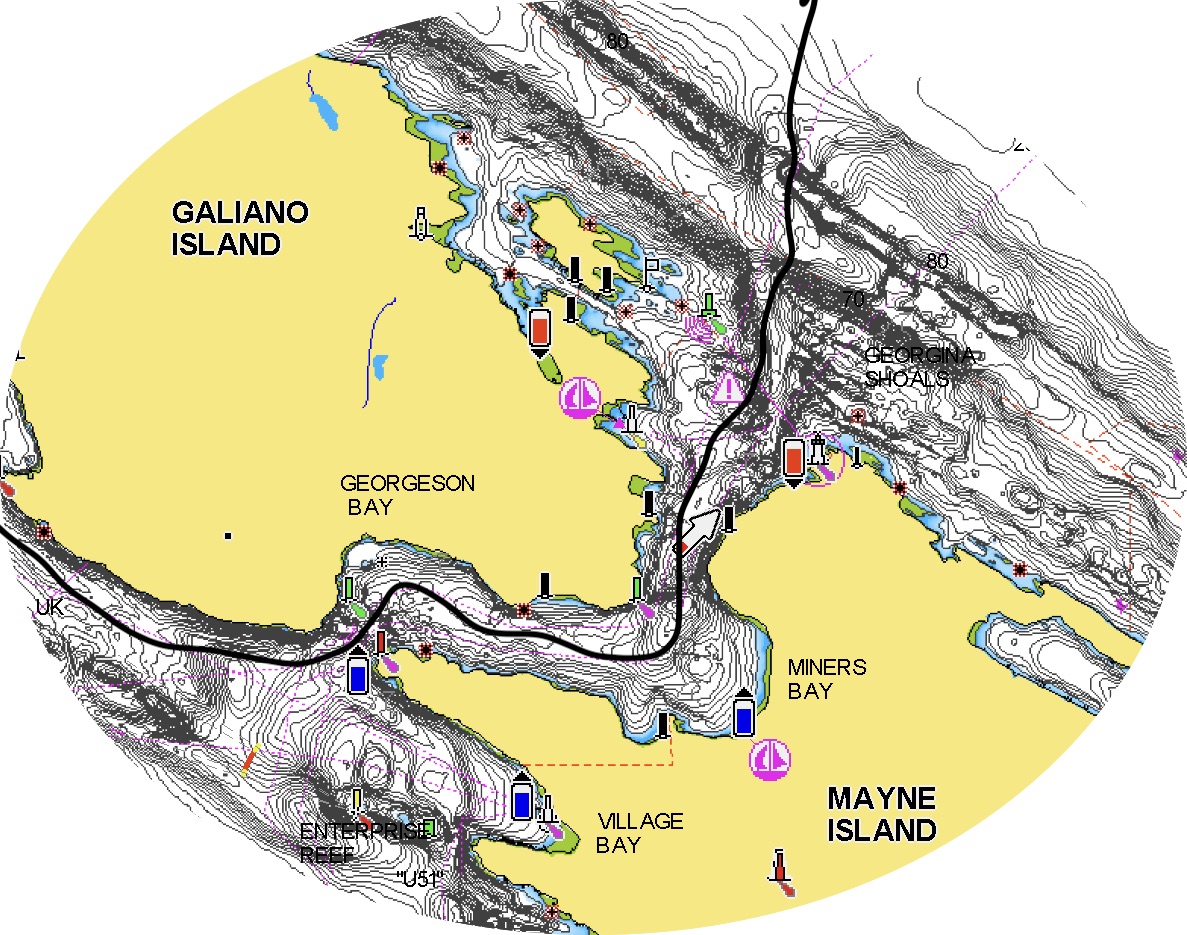

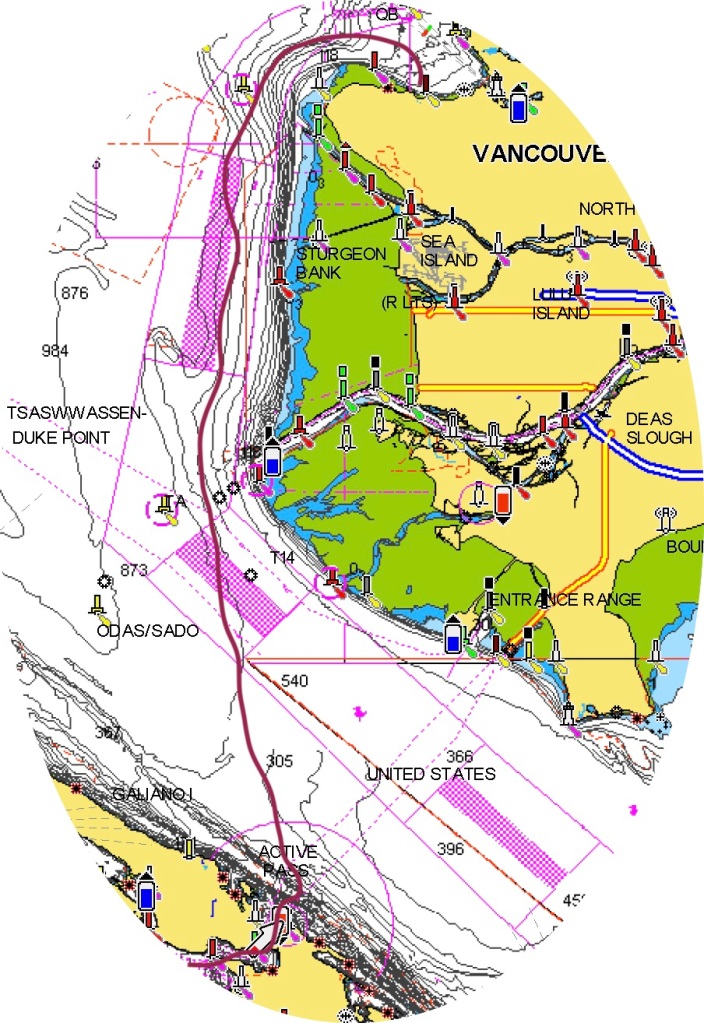

We set out early Friday morning to transit Active Pass, a narrow winding strait of swift currents and regular ferry traffic that separates Galiano and Mayne Islands, and allows passage into and out of the Strait of Georgia or the Salish Sea, as it is also known, after its first inhabitants. From there, we would angle towards the mainland, crossing the large ship traffic in the shipping lanes. We’d skirt the shallows of Roberts, Sturgeon and Spanish Banks, which lie quite (deceptively! surprisingly! beware!) far into what looks like open water, and then turn up into Burrard Inlet. Eventually we would find and dock at the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club Jericho Beach Marina. Loners rather than joiners by nature, we were astonished to learn that reciprocal privileges from our humble Sidney North Saanich Yacht Club membership would allow us to stay in Jericho Beach for several nights–a benefit easily worth the cost of our annual SNSYC membership. Our plan was to see friends, pay a visit to Costco and other retail outlets to lay in several months of bulk essentials from batteries and band-aids to pasta, olive oil, coffee, chocolate, beer, wine and tea, and to enjoy Vancouver until our elder Elisabeth arrived, when we would depart for Desolation Sound and ports north and more northerly still.

It was a thrill to navigate through Active Pass for the very first time on our own; even at slack tide the currents eddy through the winding pass. Orcas regularly transit the pass, along with ferries and plenty of other traffic; there’s always something to watch, and to watch out for. Once through the pass we raised sail. The seas were flat and there was just a puff of wind, around 7 knots or so, just enough to sail nicely out into the Strait of Georgia. Quite soon we noticed something peculiar: up ahead there appeared to be a line in the water. It looked like a zone of shadow, an abrupt change in the colour of the water; a ripple of current ran along its edge. But no clouds shadowed this line, nor was it a ridge of current. What was this about?

We looked around, looked at our charts and thought a bit. We concluded (correctly) that the line of muddy green water before us marked the extent of the outflow from the Fraser River; indeed, in late May and early June, when the outflow is the strongest, river water flows nearly all the way across the Strait, sediment bearing fresh water slipping above heavier saltwater below. We passed, in moments, from burbling blue seas to flatter calmer greens which became brown as we more closely approached the mouth of the river.

Ferries passed back and forth between mainland and islands; a coast guard vessel appeared to be stopped in place on a fishing bank, and a few other sailboats and pleasure craft were visible in the distance. We angled northeast across the shipping lanes.

Now the peaks north and east of Vancouver hove into view from beneath thick clouds clustered at the mountain tops, where melting caps and crevasses of snow were still visible. We eased towards the mainland, now out of the influence of the Fraser River currents, the wind on our beam. We picked up speed and suddenly, there was the city.

The Jericho Beach marina seemed a bit tricky to find at first; there had been some renovations since our charts had been made, and because we’d never sailed in these waters before, we weren’t at all sure of the distances and landmarks that confronted us. But then after a bit there it was; we dropped sail, radioed in and arrived at dock, our friends Janice and Mary already there to catch our lines.

A huge old club sheltered by pylons from the open harbour and named for a nearby beach, at Jericho Beach Marina we felt as though we had one foot in the wild and one foot in the city–it seemed a spectacular and easy way to visit Vancouver, albeit, not exactly “free parking.” After a few days, we realized that there was a perfectly serviceable anchorage off of Jericho Beach proper; we noted it in case we wanted to return.

We spent nearly a week in Vancouver waiting for Elisabeth to arrive so that we could set off, at last, for Alaska. While we waited, we decamped from the boat for a few nights to spend time with friends who live in the city. We hiked along the dykes in Steveston, ate plenty of sushi, drank too much, visited various regional gardens both public and private, and spent an absorbing day in the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, where we were particularly struck by a mask made by contemporary Heiltsuk artist, Nusi (Ian Reid).

Mask by Nusi Ian Reid

The mask depicts Gvna, a famous hunter and trapper and Qvumuk’ma, the King of the Sea, at the moment when Qvumuk’ma swallows an (indigestible) super tanker that has intruded on their sacred waters. Created for the occasion of a pipeline project hearing in Bella Bella, home community of the Heiltsuk Nation, the mask was designed to communicate and support the Nation’s opposition to the proposed Northern Gateway Pipeline, which would send some 200 supertankers a year carrying unprocessed bitumin through nearby coastal waters. We’d been in Bella Bella the previous year, and had also visited Wright Sound, the dangerous, beautiful and turbulent meeting place of seven waterways a day’s sail or more north of Bella, through which, had the pipeline project gone forward, those tankers would pass. Residents of Indigenous coastal communities in the area were for the most part opposed to the project, as were we, for it would mean that all those tankers, irrespective of wild weather and other significant navigational challenges, would be under pressure to go to sea. Those who knew the navigational challenges and channels were warning that, should the project go ahead as planned, a catastrophic oil spill was only a matter of time; worse still, raw bitumin sinks, and really cannot be cleaned up at all. As we’ve seen, coastal British Columbia is so beautiful and so extraordinary; there is so much life in its waters and coastal lands–why in the world should the province or its people agree to threaten all that for short term oil profits? Surely, we can be smarter than that.

After a few days on land, staying in friends’ houses, we began to miss being on the boat, for being indoors insulates you from the world. We’d been on the water for nearly a month to this point, close to birds and sea creatures, every moment dictated by the moods of the water and the weather, to which we’d had to adapt. And then suddenly we were navigating city traffic, emotional minefields, small potted gardens and the onset of depression. It felt as if we were losing the days in the dark, sitting in chairs. Indoors, the storms were all emotional; we felt buffeted by historic tornadoes, antique line squalls, a fierce wind hiding behind a chair. We felt surrounded, in tiny spaces, by swirling human relations and the weather of heartbreak. So we returned to the boat and began to provision, feeling a bit as if we’d been neglectful, as if we’d left a dog tied to a shed and failed to check on her. A day back on the boat and we felt, despite lowering clouds and spitting rain, that we’d somehow magically slipped back into our own skins.

At last Elisabeth arrived. We settled her in her cabin, had a last celebratory meal with friends and prepared to cast off the next morning. But first, while we had many hands and some space thanks to a departed neighbouring vessel, we roped Quoddy’s Run around, so that her bow was pointed towards the marina exit–one less complicated maneuver to the make in the morning. Our friends Kevin and Carmen, confirmed landlubbers, joked that they had taken part in the very first “leg” of our Alaska voyage with us. No such thing as being ready to go then: we had already departed!